Chemical Code a blog about simulation and programming

When Next-Gen becomes Current-Gen, what becomes Next-Gen?

Disclaimer: The following post contains references to my job at Covestro, but all the information herein was already disclosed at several scientific or industry conferences. I am not affiliated with AVEVA and mention their products only for explanatory purposes.

In my day job I have been working on a long-term project concerning the reorganization of our computer-aided process engineering (CAPE) software landscape at Covestro. What began with a market analysis and user survey in 2016, soon grew into a full-scale software roll-out project.

My quest for a next-gen software

When Covestro separated from Bayer in 2015, it became apparent, that the company had to re-evaluate some decisions made in the past concerning digital tools for process simulation and design.

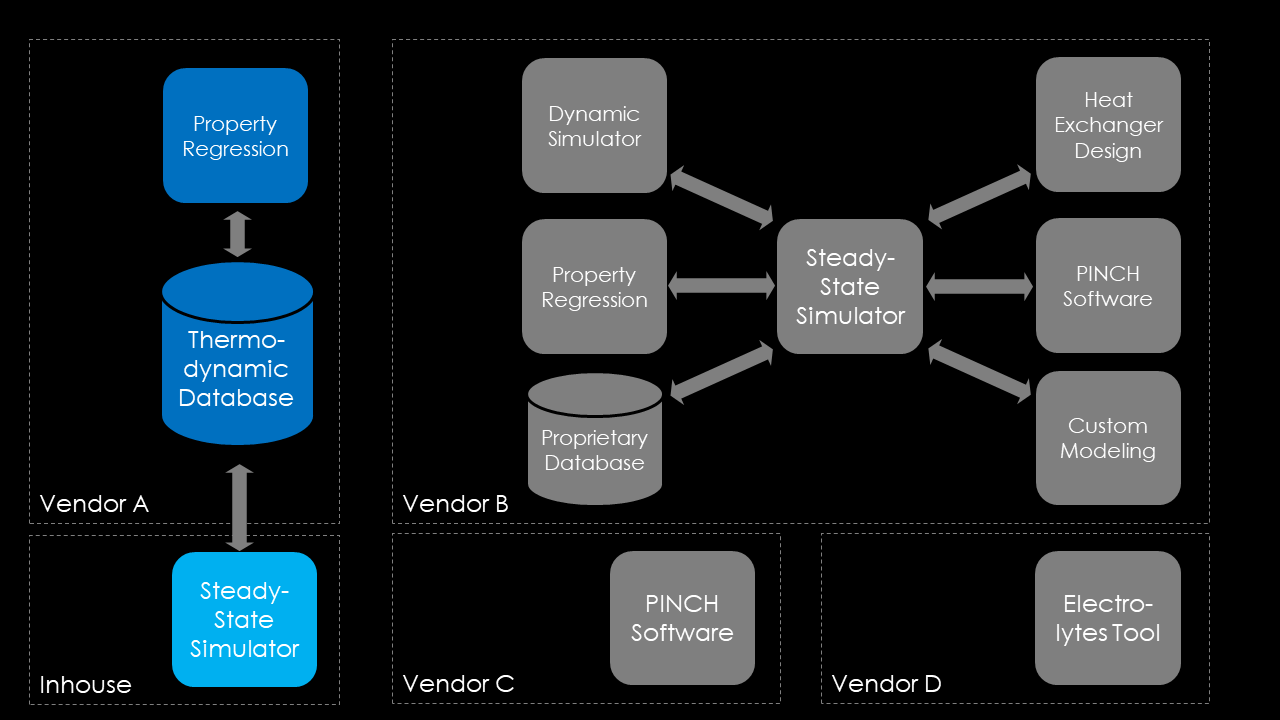

Our legacy commercial simulator began to show the marks of time. It massively grew horizontally, to support more and more applications, while it remained a large and inflexible monolith in the core. More and more modules were “tacked on” and integration never really reached acceptable levels of maturity. Switching from one tool of the suite to another required expertise, time and caution. At the same time, support for the core features that were critical for Covestro, like numerical performance, the equation-oriented solver and writing custom equations were developed at a much more relaxed pace.

In the image below, you can see a diagram showing the challenges associated with administering, provisioning and operating a large piece of complex, monolithic software, especially when you need to integrate it into a larger enterprise infrastructure. The monolithic software (or suite) has a high internal cohesion (ideally all parts work nicely together), but integration with third-party software is challenging.

At Covestro, we looked at our main application for CAPE software and decided we needed a software that could provide the following features:

- Equation-oriented solver: We have to solve large-scale, tightly integrated flowsheet models that are difficult to converge with classical sequential modular algorithms and take a long time.

- Open equations: We need to be able to bring our own IP into the simulator, and we cannot resort to classical methods like VBA, inline Fortran code, or writing COM-wrappers around custom implemented simulation code.

- Seamless dynamics: In order to solve challenging real-world support cases, engineers will need dynamic simulation tools to understand the behavior of chemical plants, especially in cases where steady-state simulation doesn’t cut it anymore (controller design, process upsets, transient operating states). We need to have both use-cases supported by a single piece of software and cannot afford to switch between two different products anymore.

- Ease-of-use: We need simulation building environments that enables every engineer, from process research, over engineering to production to solve simulation problems that are relevant for his domain.

A challenger comes to the rescue?

Our market research revealed a potential challenger, a software that claims to be the true next-gen process simulator. SimCentral promises to deliver the features that we demanded from a process simulation software, and so Covestro decided to embark on a digital transformation journey in 2018 to establish SimCentral as the main-line process simulation tool. You can find a video that summarizes Covestro’s position on the decision to switch to AVEVA SimCentral on YouTube.

From my personal point of view, SimCentral will be ready to challenge the existing competitor tools for process simulation in the next year. At this point, all of the required features for supporting steady-state simulation will be available.

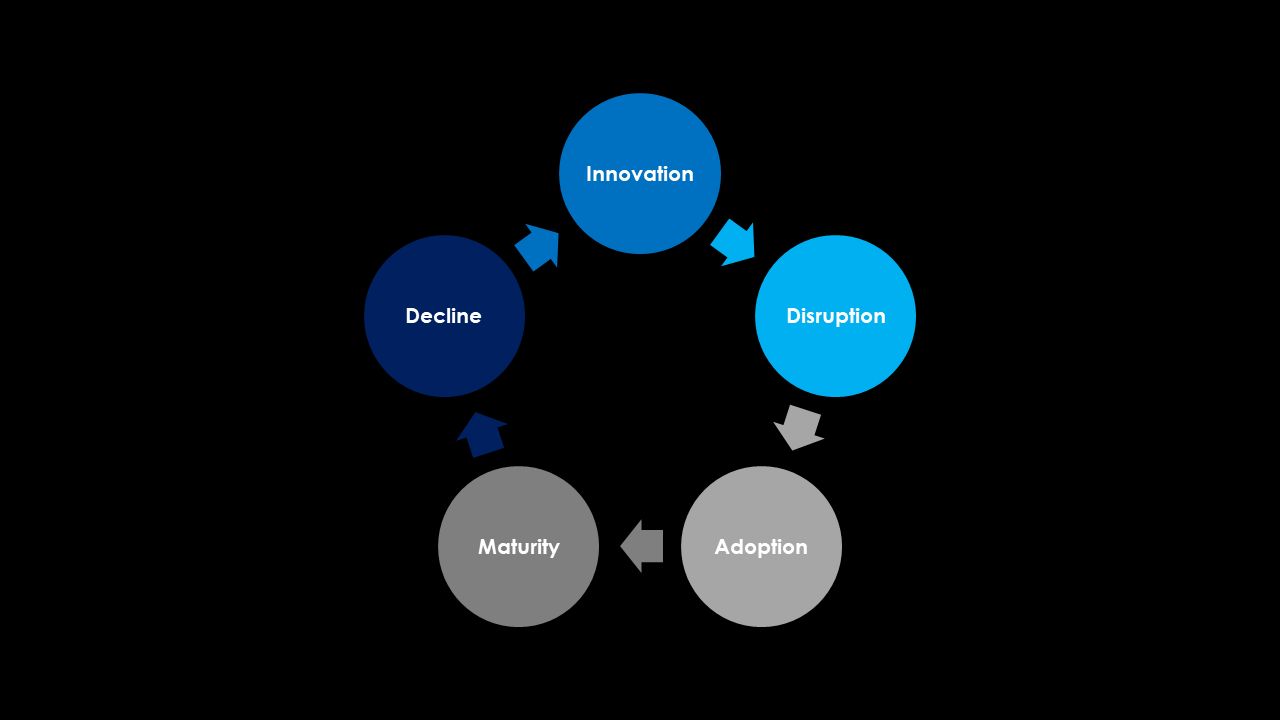

But what happens then? When the software reaches the mainstream market, it will stop being “next-gen” and become current-gen, possibly relegating the competitor software to last-gen status.

What about future-gen?

So, with the next-gen label being free again, what features could possibly fill that void? Allow me to make some conjectures about desirable features of the process simulation software of the future. To be truthful, one most admit that the chemical industry is not very advanced in digital topics. We have largely profited from past successes, when process simulation became one of the success stories of computerization. Most modern advances in technology never reached the process technology departments and are just now pushing into the operational technology (OT) world.

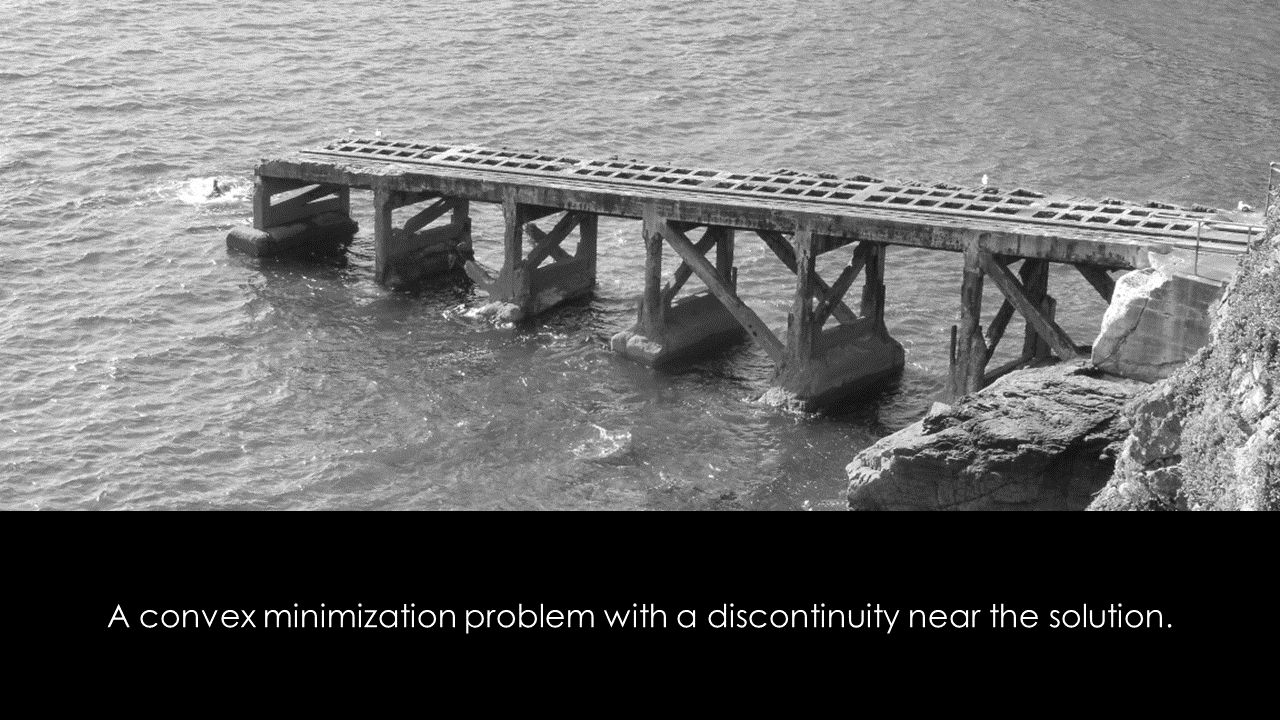

Sometimes I feel that computer-aided process engineering took the easy, downhill route in the last 15 years, and did not push enough for innovation to be transferred from academia to the industry. We were content with the tools we had and followed along. Are we currently facing the discontinuity mentioned in the (slightly tongue-in-cheek) image below?

In order to guess what the future-gen looks like for process simulation, one can look at the current-generation of software products in other industries, in this case the internet technologies. With the advent of cloud technology, a profound change in thought ripped apart the old structures of data centers and server farms. Software engineers developed technologies to increase re-usability and composability of software, and modern work processes like agile development and Continuous Integration/Continuous Development (CI/CD) reached maturity and the mainstream market. Let’s take the current state of the internet technology as a model for the future CAPE systems.

In the following I will detail a few of those points that seem to be the most important for me.

Service-orientation

The software landscapes of current technological leaders in the software sector are highly distributed and broken down into small, independent systems called services (or micro-services). Services communicate with each other with messages sent over open communication standards (HTTP/REST) but do not enforce strict dependency on specific instances of another services. When a service stops operating for whatever reason, another instance can spin up and take over.

Only with this high level of isolation and reduced inter-dependency can the performance and reliability requirements of modern applications be achieved. For CAPE software this would mean the vendors would need to break open their old monoliths and re-bundle them as a set of interconnected services that the users could consume according to their needs. More importantly, the services provided by different tools from different vendors should be able to communicate with each other.

Open-Source software

Today, most professional software runs on open-source software, from operating systems over middle-ware to front-end libraries. The free-to-use components are aggregated in ever-new ways to form new products that are sometimes monetarized.

CAPE software, on the other hand, is most often proprietary and requires expensive licenses. Scaling is much harder to achieve when every instance of the simulation tool requires a substantial expenditure. Current licensing schemes are rarely flexible enough to discern between user-bound interactive use and deployed automated use. In my opinion, licensing schemes must consider the size and complexity of the model and degree of automation. If I want to monitor a valve with a first-principle model instantiated with some pressure and flow values from the process historian and run that simulation in the loop, I would be hard pressed to sacrifice a full license for that application alone.

Platform independence

From my point of view, the modern internet would not be possible, if open-source operating systems like Linux would not exist. The scaling principle of the microservices require more and more independent execution environments, that would normally require huge amounts of license fees if a Windows operating system would be used instead. But that fact requires that suitable software is available for such operating systems. Whereas the internet industry sustains a wide range of platform independent applications, CAPE software typically runs with the old model of a locally installed client on a Windows machine.

Automation

The internet world is heavily automated. Build-scripts aggregate, compile, compose and deliver software components fully automated, sometimes even from the development directly to production, because tests, quality control and deployment are fully automated, too.

In order to reach new levels of productivity, automation in the CAPE domain has to increase dramatically. In the current state of affairs, engineers (typically highly paid experts) operate the process simulators while sitting in front of their machines, testing different scenarios and design cases, all the while being totally pre-occupied with that task, as many manual interactions are required. I think every process engineer knows the fact that many times, when a simulation run is started, he can go fetch a coffee to wait until the result is available.

With better support for scripting and automation, the engineer could design the in-silico experiments he wants to analyze up front, push the cases onto a computation-cluster and receive the result as soon as the machines are ready, freeing him up to perform other tasks while the machine labor away. Why can software engineers spin up Docker images and deploy them on a cloud in minutes, whereas the chemical engineer has to painstakingly enter each number by hand?

Of course, the simulation software must be robust enough to handle crashes/invalid specifications and all other kinds of random errors gracefully, a challenging task that is from my point of view not satisfactory solved by any software.

Open communication

Some features are already available in current-gen software. Some simulators provide COM Automation servers that allow clients to connect to the servers and perform certain tasks. But COM is outdated, heavy-weight and badly documented. In my opinion we need open, light-weight communication based on HTTP to maximize the potential of any client to be able to consume services provided by CAPE software. On the other hand, I think it is necessary that certain states in the process simulator could or should trigger events in remote systems, without the need for the vendor to implement a proprietary interface, when a simple webhook sending a JSON payload would suffice.

A possible scenario?

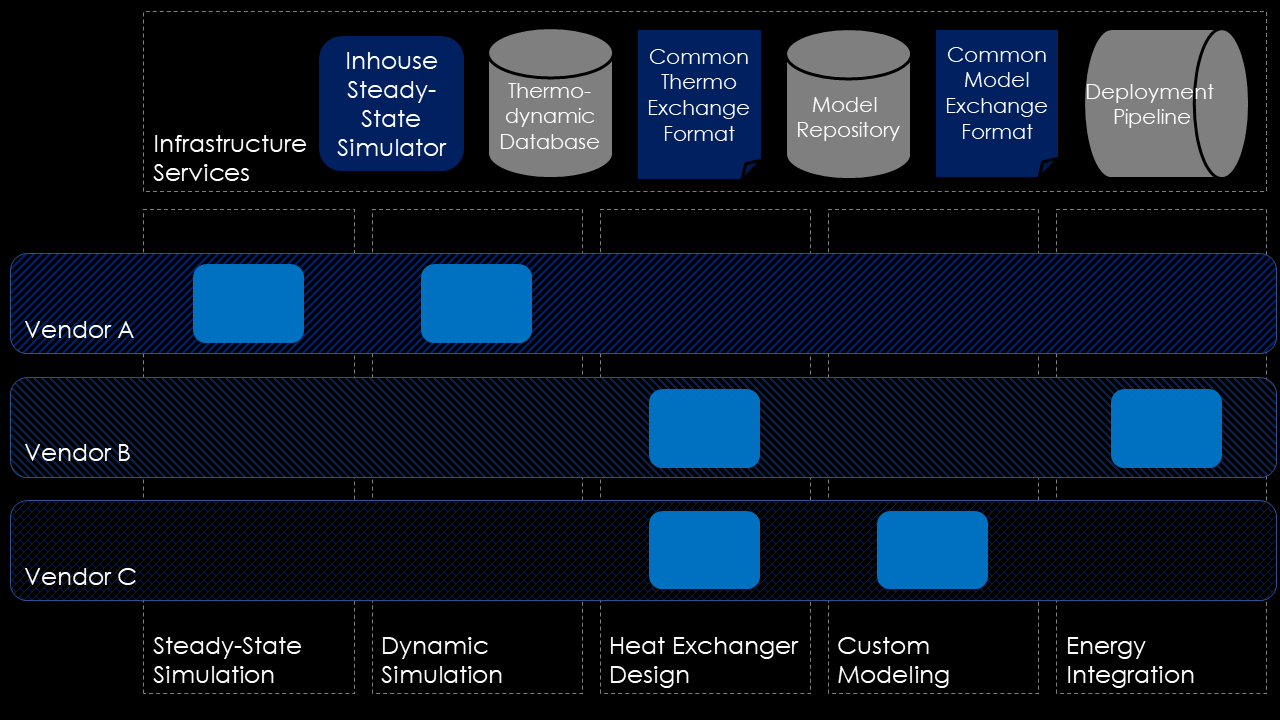

So, by now we have explored a lot of possible future development scenarios for CAPE software. But what is realistic? What could we possible achieve in the next decade? How could a modern, service-based CAPE landscape look like? My vision is summarized in the diagram below.

What features are necessary, to achieve a decomposed, standardized, open software landscape for CAPE software, as shown in the figure above? In that vision the CAPE software landscape is organized by use-cases for which each vendor could provide a specialized solution. The users could pick and customize their landscape according to their personal preference, monetary constraints, or technological features.

To facilitate interoperability between the tools and use-cases an open standard need to be defined to enable the exchange of thermodynamic property data between tools. Furthermore, a standard for the exchange of flowsheet connectivity and configuration needs to be established, in order for us engineers to be able to work on the same model with different tools.

Summary

In my opinion, the industry must come together to formalize open standards for communication. It already began in certain areas (e.g. DEXPI for CAE application, or the CAPE Open Initiative. But before we have an internationally accepted interchange format for flowsheet modeling, connectivity and configuration a lot more work has to be put in by both the vendors and the chemical industry.

Automation and deployed applications are gaining more and more importance. We will see an increase in the number of plant-level simulation applications in the coming years, as the chemical industry needs to tackle equipment maintenance and process performance challenges. Without automation and open communication this problem domain will not flourish, as the applications would be limited to what the vendors can (or choose to) offer.

tl;dr: Next-generation process simulation tools coming to the market in the 2020ies must consider current technological standards, like scalability (cloud), open communication (HTTP&REST), platform independence and novel licensing structures to enable engineers to solve the problems of the future.

Written on December 21st , 2019 by Jochen Steimel