Chemical Code a blog about simulation and programming

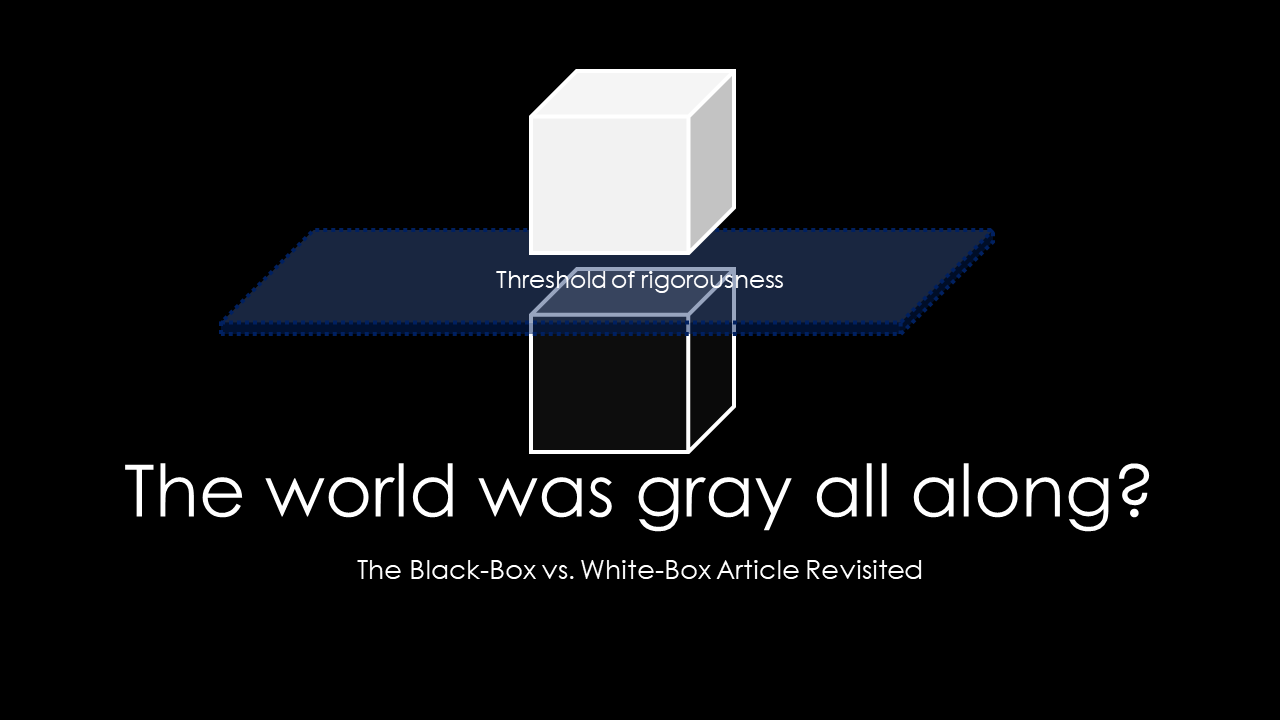

The world was grey all along? My Blackbox-vs-WhiteBox article revisited

Introduction

Roughly a year ago, I wrote a rather technical article about black-box vs. white-box models in process simulation which ended on the notion that process simulators should start including machine-learning models in their repertoire of tools. In this article I expand on the idea and talk about some practical examples.

Time for a hot-take! Quite often I get the response from experienced process simulation users (preferably those that experienced the AI-winter of the 90ies) that all this newfangled machine-learning nonsense has been tried in the past and never worked and probably never will. And that we (the young engineers) should just stick to first-principle modeling and simulation instead of wasting our time.

But then I wonder: isn’t process simulation a specialization of data science? Born in a time when compute resources were limited and expensive, and clever shortcuts had to be implemented to make the problems tractable at all? Apart from the obvious laws of mass and energy conservation and geometric calculations there is a whole lot of empirical knowledge involved in process simulation. While of course there is a physical interpretation and logic behind the Antoine equation, it still is a regression, because at the time, science could not predict the vapor pressure of a molecule just by its structure. Molecular dynamics may begin to change this, but for the foreseeable future we will be using this hybrid grey box models of process simulation.

Nearly all models used in process simulations exhibit this “threshold of rigorousness”, i.e. a point at which the predictive capability has to be augmented with regression because scientists haven’t yet come up with a clever way to describe the behavior with simple formulas.

The limits of simulator thermodynamics

The fact that we are using specialized regressors like the Antoine, Wagner, Watson and Racket equations instead of universal approximators like Neural Networks is probably a leftover from the time before ubiquitous computation. While it was a very valuable and desirable property to be able to extract the parameters for the Antoine equation graphically from (logarithmic property vs. 1/T)-plots, and the limited number of parameters proved beneficial in the early days of computing (before automatic differentiation made gradient descent super cheap), current advancements in technology and numerical methods have opened up a whole new world of tools for the process engineer.

In the KEEN project (in which I participate), researchers are experimenting with using the Matrix-Completion-Method (of Netflix-Problem fame) to predict activity coefficients in infinite dilution. While we still need the physically motivated model to calculate the mixture properties, we are (in some cases) no longer bound to regress individual binary system parameters from measurements but can directly use the values predicted by the machine-learning models.

And this observation generalizes: at nearly any point, the classical thermodynamic methods reach a limit of predictive capability and parameters regressed from experiments have to be introduced. With ML techniques, whole new classes of multivariate regressors/predictors become available, most of them with highly performant numerical implementations (even with derivatives, for those inclined to equation-oriented simulation!).

Applications for unit operations

Apart from the thermodynamic properties, empirical correlations are used extensively in equipment design, from pressure drop correlations over heat-transfer-coefficient models to reaction kinetics. In many cases we already use grey-box models with physical motivation, enhanced with regressed parameters to explain the last few percent of observations for which we have no theory (yet).

And I am wondering know: can we get better models when we allow ourselves to use better approximators/predictors than our classical, manually-optimized equation forms? Will we use convolutional graph networks (see Schweidtmann et al) to represent our physical properties based directly on the molecular structure instead of some manually derived features (like group contributions)? Will we be able to train neural networks for heat-transfer-correlations instead of using the equations of the VDI Wärmeatlas or TEMA?

The low hanging fruits

Of course, the most obvious use of machine learning methods in process simulation is for predicting properties for which no physical model exists at all, for example:

- correlating the color of the product with production/recipe parameters,

- correlating the rate of fouling in a heat exchanger to the current operating/design parameters based on a learned representation of live production data,

- correlating the rate of catalyst deactivation (from historic data) as a function of process conditions to optimize the runtime of a reactor.

In all of these cases the rigorous process simulation model is enhanced with a data-driven model trained from production data. Interestingly the machine-learning model is not used directly in the production environment for process control purposes or KPI prediction. Instead, it is used in the process simulation department with the intent to improve the process itself and not the implementation of the process (the chemical plant). Here instance-specific data (taken from production units) is used to improve the abstract, virtual process.

Conclusion

While we may have seen a time of AI-disillusionment mainly caused by inflated expectations and limited computational power (at the time), the time is now ripe to bring process simulation to the next level. Successes in other industries put the pressure on the process industry to catch up and innovate one of it’s core disciplines: process simulation.

There simply is no need to stick to only the old methods and process engineers should begin to adopt and cherish the new tools that are now at their disposal. Software companies are already on the move and start integrating machine-learning methods into their tools. It will be only a matter of time until the fast-moving companies will use those tools to achieve competitive advantage.

Written on January 23rd , 2021 by Jochen Steimel