Chemical Code a blog about simulation and programming

Evolution of flowsheet topologies - Part 1: Introduction and Overview

A while back while browsing YouTube videos, I came upon an upload that featured how a genetic algorithm would create and train a neural network to play the game Super Mario World. In this video, the author was talking about an algorithm called NEAT (Neuro-Evolution of Augmented Topologies). While at first, I was intrigued only by the playful application of technology, after a few hours of thinking about the implications of that video, a revelation struck me!

If we have an algorithm that can at the same time

- create discrete topologies (node networks) from scratch and

- optimize weights and biases (continuous parameters)

we theoretically have everything in our toolbox to synthesize chemical process flowsheets. This topic fascinated me during my PhD time and I am still a bit sad that industrial process synthesis today is still largely a manual task without much tool support from software vendors. Most of the time we are limited to comparing a few solutions that we can come up with and implement in a simulator with the limited amount of time we have. A higher degree of automation could save us engineers from the boring tasks of setting up models and getting them to converge, and bring us to the interesting part quicker, which is: developing the best process.

In 2017 Thibaut Neveux published a very interesting article called Ab-initio process synthesis using evolutionary programming. In this contribution Neveux presented a new approach for Process Synthesis, where no superstructure needs to be assumed and the flowsheet is automatically constructed. During the search, mutation and selection operators create and filter new candidates. The algorithm was implemented directly in Fortran without embedding into any modeling environment.

When I read that article first, I was very enthusiastic, but quickly I realized that it was very limited in scope. The models used in the case study are very basic and the basic problem of bootstrapping a simulation from scratch still remains unsolved. The evolutionary algorithm relies only on mutation for exploration and no cross-over operators are implemented.

After combining these two new pieces of knowledge in my mind I spend some time researching the NEAT algorithm. I read the original paper from 2002 by Stanley and Miikkulainen and (of course) watched some YouTube videos explaining it in a more approachable form. I can highly recommend the combination of reading papers and watching videos that explain the topic. For me the mixture of media really helps in understanding the principles, because I can see them working in action.

I decided to give this topic another try in the coming months to see what I can come up with. As the scope of this research topic is so broad, I will split the contents up into several blog posts that will follow roughly the agenda given below:

- Genotype representation and phenotype mapping: How to represent a flowsheet in as few numbers as possible

- Phenotype evaluation and simulation bootstrapping: How to bring a flowsheet to convergence automatically

- Mutation: How to generate new solutions

- Crossover & Speciation: How to retain good (sub) solutions

- Creating a model library: How to upgrade simulation models into design models

- Putting it all together

As for the case study, I plan on using the design of a separation sequence for zeotropic mixtures (maybe because I work in a Distillation group in my company). This problem is rather well defined, and lots of work was already put into this subject. If you want to refresh your knowledge on that subject, I can recommend a YouTube video of a lecture that explains the topic concisely. While that video focuses on the heuristic design rules for sequencing separation steps, the same principles apply for simulation-based design: in our case the algorithm will hopefully learn the heuristic rules embedded in the model and the cost functions.

For the simulation engine, I will be using my toy-simulator MiniSim because it is so easy to extend and work with. Using the integration into Jupyter Notebooks I can quickly create application prototypes and save time by not reimplementing standard algorithms for plotting or graph analysis. Furthermore, the numerical performance and stability for the kind of process talked about here is already acceptable.

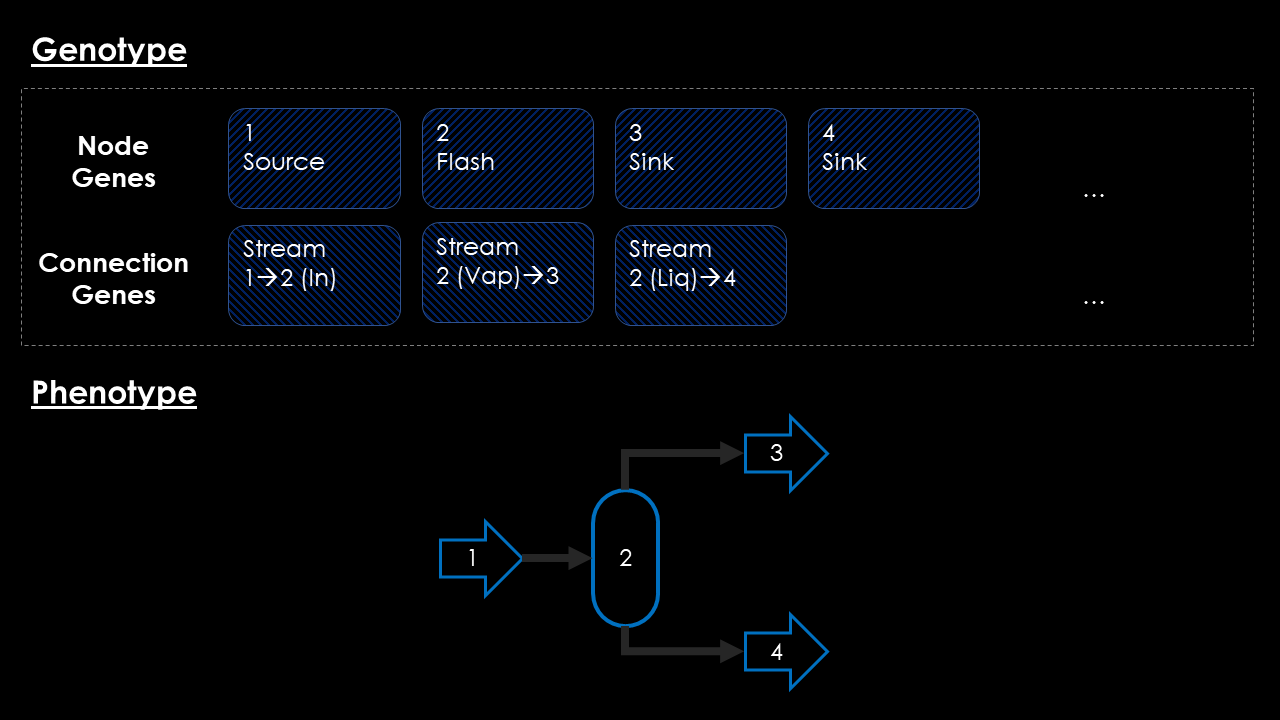

In the next installation of this article series, I will be looking into the genotype representation of topologies. Whereas Neveux uses a rather mathematical approach based on vectors and connectivity matrices, I will be using an object-oriented model based on the original ideas proposed in the NEAT article: two sets of genes represent unit operations and connections between them separately. A very simple genotype and resulting phenotype is shown in the image below.

As work has already started, it should not take too long for the next article. So, stay tuned and in the meanwhile contact me if you have any questions or remarks. I would be happy to discuss this topic with anyone interested as I am just embarking on another journey of “playful exploration”. Maybe there are limitations I am not aware of, or you know of other articles that may be relevant?

Written on January 12th, 2020 by Jochen Steimel